Two days after her father passed away, Diane Rush plopped herself on the floor of her parents’ Point Loma home, comforted by the silence in the room he once occupied. She sat there, just before 6:30 a.m., leaned against the wall and looked at the wooden floor where the hospital bed used to be. The bed’s gone now, but the books aren’t. They’re still there, grouped together by topic and neatly lined up on the shelves of a wall-to-wall bookcase.

“The variety of books that he has on those shelves,” Rush recalled, everything from writing and sailing to photography and travel. “I sat there on the floor, and I just looked at the different kinds of books. He had this amazing zest for learning — and for life.”

That’s what she remembers most about her father, Art Myers, a longtime physician-turned-photographer who trained his camera lens on many subjects but most notably women with breast cancer, orphans in Kenya and women with HIV.

Early on June 9, surrounded by family, Myers died at home from complications of Parkinson’s disease. He was 89.

Advertisement

Advertisement

“His work, whether it was through his writing or his photography, gave voice and visibility and optimism to people experiencing hardships,” said Rush, who lives in Escondido.

A new calling

Charles Arthur Myers was born on Oct. 18, 1930, in Cucamonga, now known as Rancho Cucamonga, in San Bernardino County. He was the son of a Church of the Brethren minister and a stay-at-home mother who later worked as a music therapist at an Ohio state institution once Art got older.

From his parents, Art Myers learned how to help.

“They did a lot of volunteering,” Rush said. “His mom and dad were like that — helpers. They were humble people. Moved around a lot and had no money, but they were always willing to lend a helping hand.”

Perhaps that’s why Myers chose a career in medicine. In 1953, he received a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Akron before pursuing a doctorate in osteopathy, graduating from Philadelphia College of Osteopathy in 1958. He completed a residency in internal medicine at Flint Osteopathic Hospital in 1964 and landed a fellowship in nuclear medicine at Marquette University in Milwaukee. Later, he would become chief of staff at Northwest General Hospital in Milwaukee.

He practiced medicine for decades and had a private practice in Mission Hills. He then worked for the California Department of Rehabilitation before retiring in 1997 at the age of 67. Most would have been content living a quiet life in retirement. Not Myers. He had another passion — photography — and retiring from medicine meant he had more time to devote to it.

Advertisement

“Even when we were little, he loved to take pictures ... ,” Rush said, remembering how camera equipment could be found all over the family’s Point Loma home. “It started out as a hobby. As we got older, and he found more time, he took classes. It turned into a very serious hobby. It was like a second career. He definitely found a new calling.”

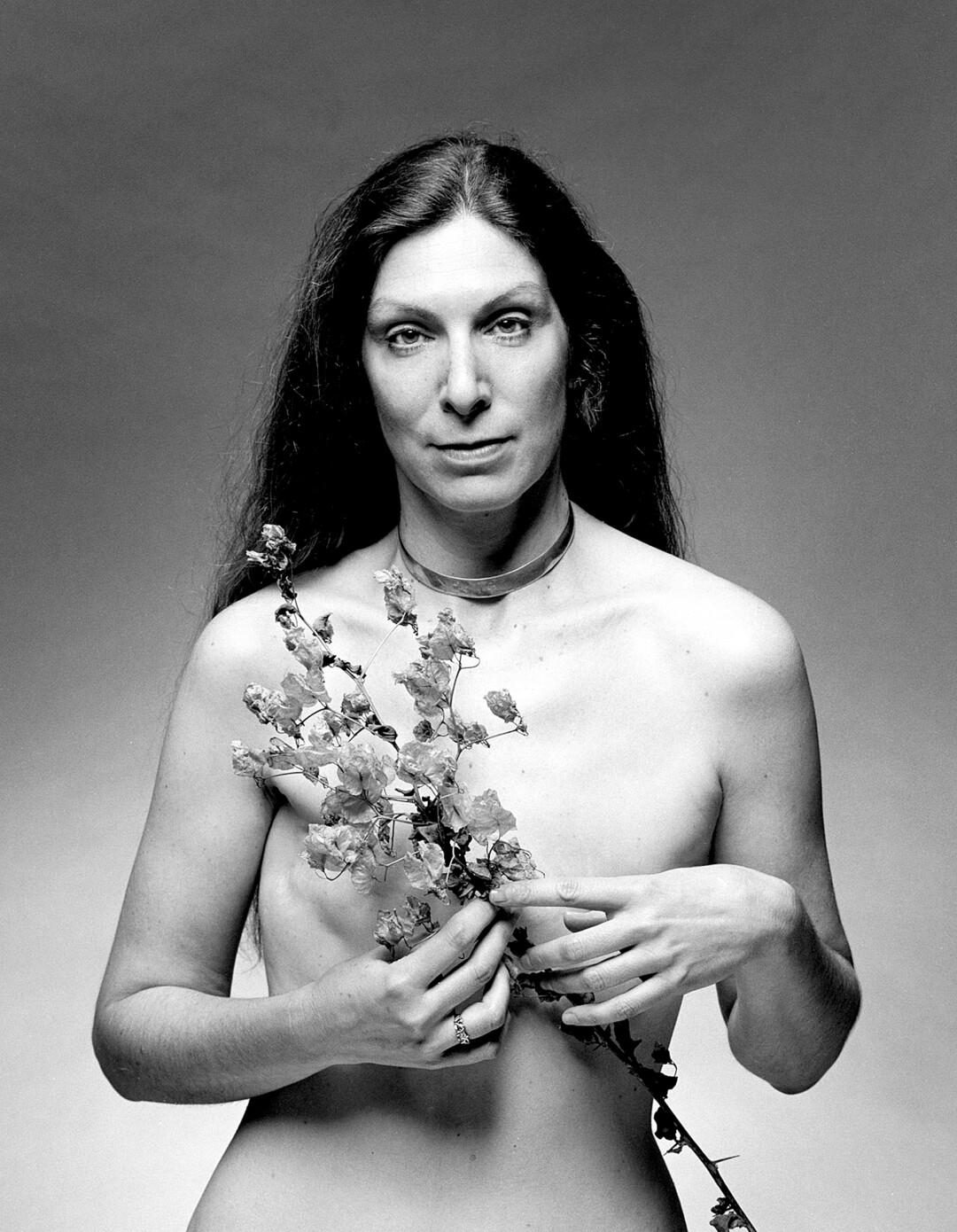

“Carol,” by Art Myers

(Courtesy of the Art Myers family)

It was personal

He worked as a professional photographer, often hired by corporate clients, and traveled all over the world, including Kenya, where he photographed children at the Nyumbani Village orphanage. But it was his work documenting the plight of women fighting breast cancer that caught many people’s attention. Those photographs were part of a series that collectively became a book and an exhibit titled “Winged Victory: Altered Images — Transcending Breast Cancer.”

The project wasn’t just another pursuit. It was personal.

“I am still haunted by the memory of the phone call from my mother telling me in a trembling voice that my sister Joanne, still in her thirties, had been diagnosed with breast cancer,” he wrote in “Winged Victory: Altered Images — Transcending Breast Cancer,” first published in 1996 and reprinted with new photos in 2009. “Following a prolonged heroic battle to survive, she was to eventually die from the disease. Two decades later, I anxiously faced a surgeon in an antiseptic hospital waiting room as he uttered the dreaded words, ‘Your wife has breast cancer.’

“In my career as a physician,” he continued, “I have many times had the sobering responsibility of delivering the news of a cancer diagnosis to patients and their loved ones. However, I was not prepared for the overwhelming effect that breast cancer in two close family members would have on my life. I began to see the disease in a new light. I learned that anxiety about survival, initially the most important worry, can give way later to a new unease both in the survivor and her partner.

“The woman may begin to cover her nakedness, fearing a spouse’s averted glance, or turn away from the reflection in a mirror that unremittingly reminds her of fears of diminished femininity. A partner withdraws a hand to avoid touching a scar where once was a graceful curve. Lovers draw apart, an absent breast now a barrier to their intimacy. A fiancé quietly turns his back and walks out of a cancer survivor’s life. These fears about body image, femininity and sexuality are understandable in a society that is bombarded by media messages of centerfolds, push-up bras and silicone implants — messages that erroneously imply that a perfect breast is the requisite icon of the feminine essence.”

“Hands of the Photographer’s Mother,” by Art Myers

(Courtesy of the Art Myers family)

His heart and his art

It was there, deep in the depths and darkness of insecurity and fear, where Myers used his camera to bring forth light.

“The message of this book is that these are still whole women,” Myers said in an Aug. 27, 1996, article in the Union-Tribune. “That whether you lose a breast or not, you don’t need to feel diminished.”

Advertisement

And that’s exactly what caught the attention of Liana Zhou, director of the Kinsey Institute Library and Special Collections at Indiana University Bloomington. That’s where an extensive collection of Myers’ work — mostly print images that have now been digitized — exists, having been donated by Myers and his family three years ago.

Upon seeing his breast cancer-themed photographs, Zhou said, “I ... instantly felt empowered by his work, and I felt it was very important for the Kinsey Institute to archive his work.”

“Something that strikes me as fundamentally remarkable,” she added, “is that he used his tool to not only provide a voice to the vulnerable or marginalized population, but he used beauty, seen through his lens, to redefine themselves. I thought that was extraordinary.

“I told myself that if I ever wrote anything about Dr. Myers, it would be about his heart and his art,” said Zhou, who came to San Diego last year to visit Myers and his family. “He was able to create dignity when, for many, that was long lost. He was able to create the fundamental ideals of hope, desire, self-esteem and, of course, dignity. That’s what I saw.

She added: “Dr. Myers dreamed of a more wholesome humanity, and he pursued that dream by building up individuals in their darkest moments in life. The women who survived breast cancer but now have to question their femininity. The women who were diagnosed HIV-positive who had to find courage to keeping on living. Or the orphans who seemed to have all lights turned off on them. Dr. Myers used his art and heart to turn on the dimmed light for them all.”

Rush agreed: “He had this innate ability to put optimism where traditionally there was none — in breast cancer, in HIV, in homeless people living in motels. He would just chat with them and get to to know them and they’d open up. He had a way with people, and it showed in his work.”

“Dance as Therapy,” by Art Myers

(Courtesy of the Art Myers family)

He fought hard

In 2003, the tremors began, and Parkinson’s would eventually be identified as the culprit.

“It was really slow at first,” Rush said. “But he fought it all these years, and he fought hard. He was going to live to be a 100, you know. This would’ve really disappointed him.”

But, in quintessential Art Myers fashion, he wouldn’t have dwelled on it. He never let anything stop him. In 1989, at the age of 59, he received a master’s degree in public health from San Diego State University.

Advertisement

“He had all these degrees and worked in internal medicine for many years,” Rush said, “but he was most proud of that — going back to school and getting that degree.”

Despite his jam-packed schedule, he always found time to help. He served on the board of the Museum of Photographic Arts in Balboa Park, and at one time, worked on the Campo Indian Reservation.

Besides photography, there were many other constants in his life. Sailing, Friday happy hours with friends and trips to Paris, where one year, 3-foot-tall banners hung on street posts outside city hall to promote an exhibition featuring his “Winged Victory” photographs. And writing — he loved to write.

“He wrote till the end,” Rush, the eldest of Myers’ four children, said. “He was working on a short piece on John Muir until the last day. He was creative and smart and fun.”

For the Kinsey Institute’s Zhou, Myers was that and more.

“Art was like a flowing river to me, someone who brought nourishment and strength,” she said by phone from Indiana. “He taught us every transition could be a transformation. He helped so many by showing us that transitions, such as an illness or a life change, can be a transformation.”

Myers is survived by his wife of 59 years, Stephanie Boudreau Myers; brother Milt Myers of Tulare, Calif.; children Diane Rush of Escondido, Lynn Mariano of Chula Vista, Chuck Myers of La Jolla and Gretchen Valdez of Riverside; eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Due to coronavirus restrictions, services will be held at a later date. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to a Parkinson’s association of the donor’s choice, Museum of Photographic Arts (MOPA) in Balboa Park, and the Kinsey Institute Library and Special Collections at Indiana University Bloomington.

Art Myers, a physician-turned-photographer, died on June 9 surrounded by family in his Point Loma home. He was 89.

(Courtesy of the Myers family)

"used" - Google News

June 21, 2020 at 07:32PM

https://ift.tt/3fHJboQ

Art Myers: How a physician-turned-photographer used his heart and his art to redefine beauty - The San Diego Union-Tribune

"used" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2ypoNIZ

https://ift.tt/3aVpWFD

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Art Myers: How a physician-turned-photographer used his heart and his art to redefine beauty - The San Diego Union-Tribune"

Post a Comment